I came to the medieval Irish tale Buile Suibhne or Mad King Sweeney not through history, not through poetry, not through language, but through music, more specifically, through song. Several years ago (everything seems to be several years ago now), Marshall Hughes, the founder of Boston’s Opera UnMet asked me to write a few pagan songs for a winter solstice celebration at The Cambridge School of Weston, a Boston area private high school where he was music director. Nothing like a nice little pagan assignment, I thought - something about nature, or drinking, or sex. I immediately began to think of possible texts and music. I also liked the idea of these songs being the beginning of something greater, part of some larger work in progress.

So, I had to go looking for the larger work. I am a great admirer of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana and have a fair bit of Latin left in me from my college years, so I began thinking of Latin texts.

I telephoned my Aunt Joan, who also knew a fair bit about Latin. For many years, she was a longstanding member of the Classics Department at Southern Illinois University. We discussed the biggies -- Horace, Ovid, Catullus. Nothing captured my imagination. Latin had been done. Then it came to me. On a recent trip to Ireland, I had visited some of the great stone circles and dolmens that dot the countryside. I stood on those barren expanses with great slabs of granite propped towards the sky and thought it miraculous that I was sharing this vast domain of rock and sky with my Druid ancestors. Only time separated our experience.

These songs need to be Irish, I thought.

Shortly after that, at a family party, I asked my O’Malley brother-in-law, then the head librarian at the University of Rhode Island, and a devoted student of Irish history and literature, “Bill, I’m looking for some kind of epic Irish poem, something with a good story, something I can set to music, you know, something…”

He interrupted me with two words: Sweeney Astray.

He directed me to Seamus Heaney’s translation.

Sweeney Astray is the story of a mad king in medieval Ireland.

I devoured Heaney’s translation of Buile Suibhne and quickly realized this was for me.

The poem had elements of fury, malediction, transformation, sorrow, contrition, contemplation, and resurrection. In Sweeney’s Praise of the Trees of Ireland I found my entering spot.

The tale of King Sweeney dates to the Battle of Moira in 637AD. It seems a certain Ronan Finn, a holy and distinguished cleric became infuriated by Sweeney’s bad behavior (Sweeney had thrown Ronan’s hymnal into the lake). The cleric cursed Sweeney, turned him into a bird and banished him to roam to desolate crags of the north country, naked and isolated.

Sweeney rails and roosts in medieval Ireland -- a whinging and angry spokesman for the stubborn Celts holding out against a rising Christian ethos. He’s a renegade who is prone to losing his temper. He flies off the handle and pays dearly for his impulsiveness and lawlessness. But then the rabble rouser turns on himself and becomes the philosopher, the observer, a man set adrift from all known places, isolated. He loses his home, his wife, his friends and is forced into bitter self-examination.

There is a heirarchy of trees in Irish lore. We are, each one of us, assigned to a tree at birth. (https://tree2mydoor.com/pages/information-trees-celtic-tree-calendar)

I decided to create a Greek chorus of trees.

Our first performance at The Cambridge School of Weston was exactly that. I roped a few neighbors into singing with me. We dragged large tree branches onto the stage and off we went!

But that was not the end. It was the beginning.

Here is Seamus Heaney’s rich translation of the description of Sweeney’s transformation. (I used Heaney’s translation. I wrote to him and he wrote back to suggest I get permission. His letters to me are another treasure!)

His brain convulsed,

his mind split open.

Vertigo, hysteria, lurchings

and launchings came over him,

he staggered and flapped desperately,

he was revolted by the thought of known places

and dreamed strange migrations.

His fingers stiffened,

his feet scuffled and flurried,

his heart was startled,

his senses were mesmerized,

his sight was bent,

the weapons fell from his hands

and he levitated in a frantic cumbersome motion

like a bird of the air.

And Ronan’s curse was fulfilled.

This tale was originally told over a campfire by the seanchaí, the story-teller, around 637AD, in the age of the Irish kings. It was not set to paper until the mid-seventeenth century. In old Irish. I got my hands on the Old Irish text and really wanted to incorporate it into the performance. But, how to pronounce it?!? I visited the head of the Irish department at Harvard. Nothing. No one knew how to pronounce Old Irish. Then, one day, while having a little pot of tea at Matt Murphy’s pub in my neighborhood, I overheard an old lady teaching Irish to Matt’s kids. I showed her the text and off she went, reading the old text. I dashed home for a tape recorder.

A taste of the Old Irish:

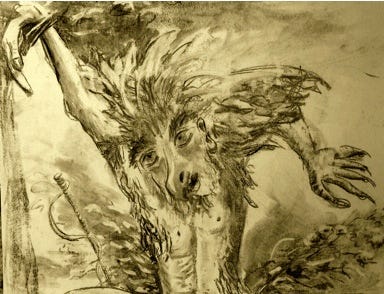

There was no illustration anywhere of mad king Sweeney, so I taped a long piece of paper up on my wall and went mad with a stick of charcoal, drawing Sweeney being transformed into a bird.

I imagined the tree songs popping schizophrenically out of the familiar background of a traditional Irish overture. Now, why someone invents what they do is a complicated mix of logic, fancy, and total unreason. I was sure of one thing; I did not want this piece, whatever it was going to be, to be an evening of traditional Irish music. Irish music is meant to be danced to, not watched. I certainly wanted a thread of traditional to run through it, but I wanted these first songs to be quirky, singable, but definitely not boring. Songs of the people.

Now the going gets a little quirkier. The music that was in my head at the time was that of Kurt Weill, the German American composer. I had just finished writing and performing an evening of his music, impersonating his wife, Lotte Lenya. Weill wrote many of the songs with Lotte’s limited voice in mind, but he loved complicated music, so his solution was to write very simple melodies that Lenya could handle but place them over a complicated bed of complex harmony and unexpected musical changes. I like that model very much -- to write simple pleasing melodies surrounded by sophisticated harmonies. I wanted to write simple melodies of everyday people, but simple melodies turned into magic.

Traditional Irish music of today is, of course, simple and straight-forward harmonically. But remember, music drifted to Ireland over the seas from many destinations -- from Scandanavia, from northern Gaul, from Spain which traces back to the Arab and African nations. And remember, this is medieval Ireland, where Christianity is trying to get a toe-hold. I had Charles Ives-ian notions of two marching bands colliding, one a group of rabble-rousing singers around a campfire, and the other a phalanx of monks, chanting their way into the consciousness of the people.

I had the good fortune to connect with Mike Finegold and his Essex Chamber Music Players. John Sullivan became my Sweeney, along with Mike on flute, David Pihl, piano and Emmanuel Feldman, cello.

In this excerpt, we hear Sweeney praise the birch tree followed by his Lament.

The notion of metamorphosis has captivated the imagination forever. From the dramatic physical transformations of Ovid or Kafka to the more subtle psychological changes of Proust or Joyce, we all hold out for the possibility of miraculous human re-creation and resurrection. But as Sweeney’s cautionary tale demonstrates, such change does not occur without costly suffering and poignant loss and no one in their right mind would enter into it willingly. It takes a curse, an existential crisis.

I am fascinated by these crucial turning points in our lives.

His brain convulsed, his mind split open.

Moments of great personal change are moments filled with tremendous feelings of disorientation. We dance dangerously close to schizophrenia. Our sense of up and down, right and wrong is jostled. Our brain is traumatized.

Vertigo, hysteria, lurchings and launchings came over him,

he staggered and flapped desperately,

We lose the sense of control we all so carefully cultivate in our lives.--a control that is necessary to maintain equilibrium and yet, in order to grow, we need occasionally to relinquish sanity. Most of us don’t have the courage to do that voluntarily. There is a desperation about it that frightens and chases away family and friends. At that moment of transformation, we are truly alone.

he was revolted by the thought of known places

and dreamed strange migrations.

At these moments, life as it existed until that moment becomes suspect, becomes the enemy of growth. There is a deep urge to move, in spite of the terror, into something new, something unknown. And these metamorphoses are never smooth. They are cumbersome, desperate and hysterical.

I flapped around with Mad King Sweeney for more than a year. He accompanied me through my own metamorphosis. I give thanks to him from my perch in a yew tree.

Wahoo! Wonderful

Intertwining of many transformations! Didn’t know about Sweeney till you told me this story once awhile back. Now to have the whole story! Fabulous, Kate. Oh the wondrous things you’ve created!

Yessiree! at The Irish Cultural Center. Canton You guys were great! Such a thrill. I have a video that needs lots of cropping. I’ll get to it soon! 😘